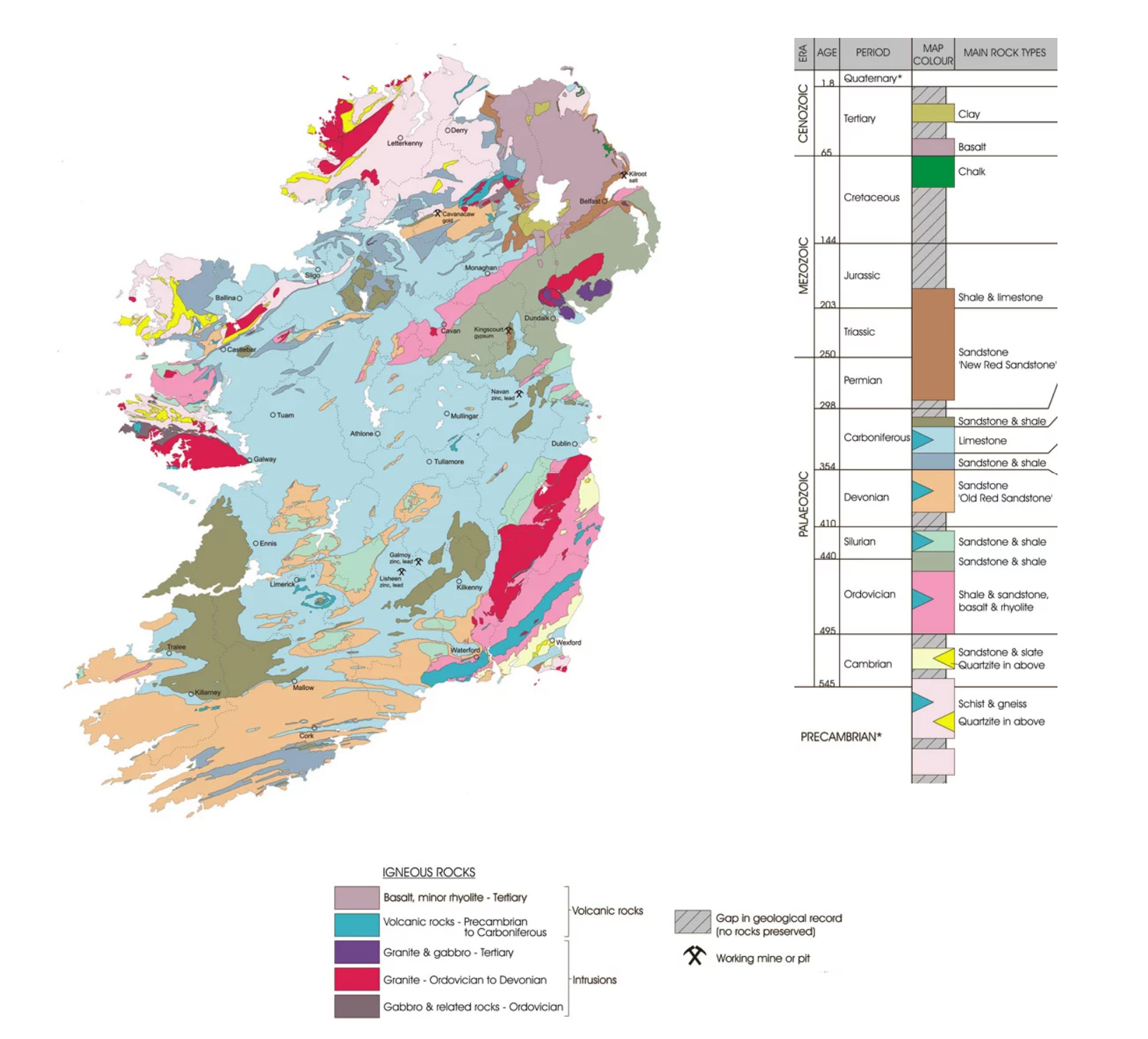

The geology of the island of Ireland is a fascinating tapestry that spans over 600 million years of Earth’s history, encompassing a diverse range of rock types, geological structures, and landscapes. From ancient Precambrian bedrock to glaciated valleys carved during the Ice Age, Ireland’s geological heritage reflects a complex interplay of tectonic activity, erosion, and environmental change.

The geological foundation of Ireland is primarily composed of three major rock types: igneous, sedimentary, and metamorphic. These rocks provide insights into the island’s ancient history and environmental evolution.